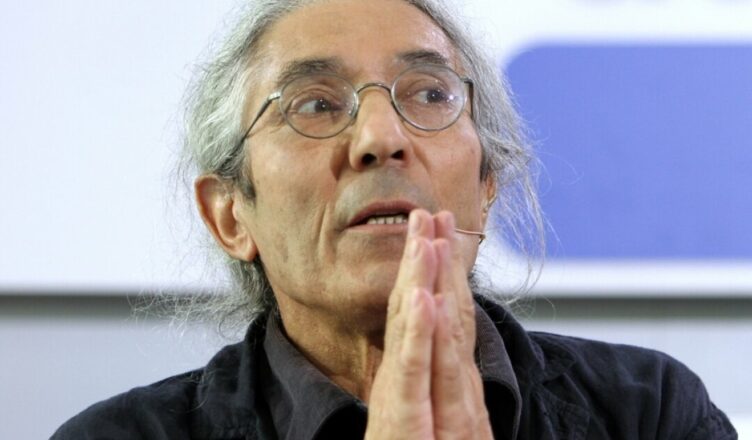

The Franco-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal, imprisoned for a year in Algeria amidst a diplomatic crisis between Algiers and Paris, was granted a pardon on Wednesday and arrived in Berlin in the evening, where he is to receive medical treatment.

The presidential pardon for Boualem Sansal, requested by Germany, is officially presented as a « humanitarian gesture. » In reality, the release, following a direct request from President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, is seen within the regime as a diplomatic humiliation and an affront to the political sovereignty that the Algerian military power claims as a red line, according to sources close to President Abdelmadjid Tebboune.

Giving in to Berlin’s demands, expressed publicly by President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, essentially means acknowledging that Algeria’s judicial decisions can be influenced by foreign pressure. The Algerian regime derives its legitimacy from a narrative of historical continuity: that of a state born from the war of independence, one that is the master of its own choices and resistant to foreign intervention.

A pardon granted following a European appeal would contradict this narrative and project the image of a government subjugated to Western capitals, especially at a time when Algiers seeks to position itself as an independent actor on the international stage. The military circles and intelligence services of General Saïd Chengriha, which form the backbone of the regime, see this as a dangerous precedent: if international pressure can sway the head of state over the case of a writer, it could later be used to influence political prisoners, journalists, or even issues like the autonomy or self-determination of Kabylie.

That is why, even though the Algerian presidency publicly acknowledges the German request, it does so cautiously, testing the reaction of public opinion and the military security apparatus. Inside the country, the regime has long used anti-Western rhetoric to justify repression and foster a national distrust. A release « under foreign orders » would undermine this discourse, portraying the government as acting not out of sovereign conviction, but under foreign constraint.

In a context of political fragility, mass unemployment, declining purchasing power, unrest in the interior provinces (wilayas), and ongoing distrust of the Hirak movement, such a move would be immediately exploited by the opposition. The military might accuse Tebboune of yielding to European pressure, and some analysts even mention the risk of a rejection of the president by the harder factions of the regime’s power structure.

On the international front, a release demanded by Germany would be seen in Brussels as a diplomatic victory for European diplomacy, but in Algiers, it would be perceived as a loss of face.