Since gaining independence in 1962, Algeria has been constitutionally defined as a republic. Yet behind this institutional framework, many researchers, observers, and political actors describe a system deeply shaped by the predominance of the military establishment.

More than sixty years after the end of French colonial rule, preceded by Ottoman and other periods of domination, the army has become the center of power, shaping the country’s political, economic, and diplomatic trajectories.

As early as the summer of 1962, the National Liberation Army (ALN), made up of groups and militias at the time of independence, quickly asserted itself in the struggle for power against civilian figures who had fought colonialism.

This dominance was further consolidated in 1965 with the overthrow of President Ahmed Ben Bella by Colonel Houari Boumédiène. This coup marked a decisive turning point: the army, initially trained and structured by French officers, and later by the former USSR and its satellite states, ceased to be merely one actor among others. It became the core of real power. From that point on, the general staff and security circles structured the country’s political, economic, and social life.

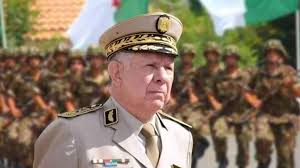

Officially tasked with national defense, the People’s National Army in reality plays a central political role. It intervenes in the appointment and removal of presidents, arbitrates major crises, and steers the state’s key strategic decisions.

Through its military intelligence services, a fundamental pillar of the regime under various names, the army exercises tight control over the political class, the media, and civil society, helping to sustain a system of constant surveillance and regulation of the political, economic, and social spheres.

In this context, civilian institutions, Parliament, political parties, and governments, appear largely subordinate. Electoral processes, regularly criticized for their lack of transparency, struggle to generate genuine popular legitimacy.

Successive Algerian presidents have often been perceived as the product of internal compromises within the military institution. Their autonomy remains limited in the face of informal centers of power. The National Liberation Front (FLN), formerly the single party and later the dominant one, long served as a political relay for the regime, without ever establishing itself as an independent force capable of counterbalancing the army.

Restrictions on public freedoms, along with the arrest of journalists, political opponents, civil society activists, and human rights defenders, represent another defining feature of the regime, justified through a security lens that frames dissent as a threat to national unity.

Economically, hydrocarbon revenues, along with companies placed under the leadership of military officers following a decree by President Abdelmadjid Tebboune at the instruction of General Saïd Chengriha, form the backbone of the system. Their opaque management strengthens power networks linked to the army and the senior bureaucracy. This concentration of economic power fosters structural corruption, which is rarely punished when it involves figures close to the regime.

On the international stage, Algerian foreign policy is strongly influenced by the army’s security priorities. While official rhetoric emphasizes non-interference, Algeria plays an active role in the Sahel and North Africa, viewed as a strategic depth. This involvement, sometimes marked by ambiguity, allows the regime under General Saïd Chengriha to present itself to certain African countries as an indispensable actor in regional stability.

As long as the political role of the army is not redefined and genuine civilian authority accountable to citizens is not established, the emergence of the rule of law and effective popular sovereignty will remain a distant prospect.